Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 18 Issue: 177

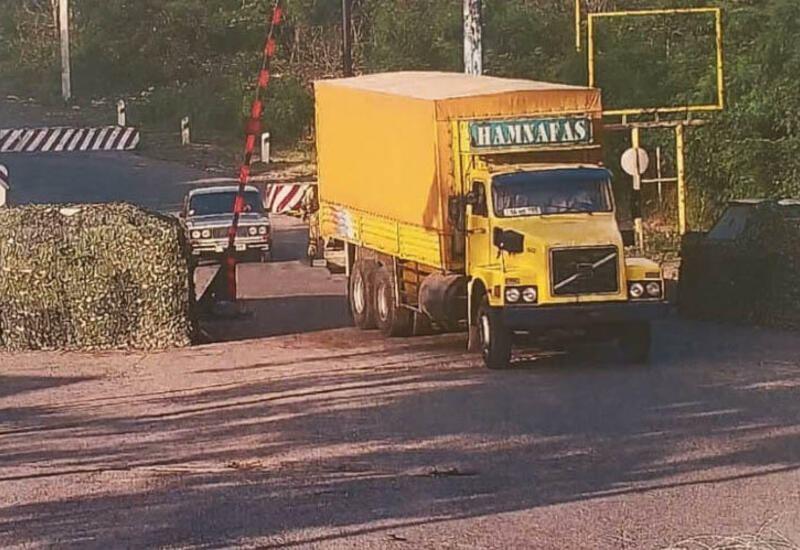

Last September, long-brewing strains between Iran and Azerbaijan reached an unprecedented level, resulting in the deployment of troops and large-scale military drills by both sides. The most immediate trigger was the Azerbaijani authorities’ arrest of two Iranian truck drivers on Armenia’s Goris–Kapan highway (which partially straddles the undelimited portion of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border) for illegally entering the territory of Azerbaijan (Turan, September 15; see EDM, October 6, 27). In addition to Baku’s and Tehran’s rival demonstrative military exercises near the two countries’ shared border, their mutual diplomatic rhetoric became even more aggressive. Inadvertently or not, Baku’s blockade of the road for Iranian trucks also notably spotlighted Iran’s energy exports to Karabakh.

For years, the Islamic Republic has supplied the Armenian-occupied enclave in Karabakh with fuel and other energy goods transported by truck—a continual source of discontent in Azerbaijan (Azvision, October 11). As for natural gas, the de facto regime in Karabakh obtains its necessary volumes for commercial and household use from Armenia, via Azerbaijan’s Lachin district, through a single-channeled pipeline. And crucially, that pipeline at least partially carries gas purchased from Iran (Vesti, December 1, 2020).

Shortly after the November 9, 2020, Russia-brokered ceasefire agreement, which ended the 44-day Second Karabakh War, control over the heretofore Armenian-occupied Lachin district transferred to Azerbaijan—although protection of trade and transit via this vital corridor (physically linking occupied Karabakh with Armenia) was conferred to a Russian “peacekeeping” mission (see EDM, January 21, 22, 26, 2021). The return of the Lachin district to Baku’s control almost immediately raised questions about the security of the Iranian natural gas flow (via Armenia) to Karabakh and prospects of dangerous energy deficits in the region. Nevertheless, Russian peacekeepers helped rebuild the partly damaged pipeline to ensure continued deliveries to the parts of Karabakh (for now) left under occupied control after the war (Vesti, December 1, 2020). Although Russia is the main energy supplier of Armenia, with further transit to Karabakh, Iran is another vital source, providing up to 500 million cubic meters of natural gas per year via the Iran–Armenia gas pipeline as part of their gas-for-electricity agreement (Newgeopolitics.org, June 18, 2021).

Apparently, the Iranian-Azerbaijani diplomatic crisis pushed Yerevan and Tehran into negotiations regarding constructing an alternative transit route for fuel shipments. As of November 11, Armenia confirmed the opening of the Tatev–Aghvani–Kapan highway, bypassing a three-kilometer stretch of the Vorotan road now controlled by Azerbaijan. That roadway had heretofore been particularly treacherous for trucks and automobiles due to the terrain (Big Asia, November 11); but, Iranian commercial vehicles have already started using this newly inaugurated route to deliver fuel and other goods.

Moreover, earlier this year, the Armenian government announced that it would allocate $1 billion from the state budget to construct another strategic route to Iran—the Kajaran–Sisian highway, which is to be part of the North-South International Transit Corridor—in Syunik province (Armenpress, September 16). It seems that Prime Minister Nikol Pashinan strives to safeguard the physical connection between Armenia and the Armenian enclave in Karabakh by relying on Iranian vocal support while avoiding confrontation with Azerbaijan. Baku, however, takes a hard stance regarding Iran using the Lachin corridor for trade without Azerbaijani consent. More broadly, Azerbaijan is unhappy over its lack of de facto control of this corridor, which is a crucial point in the current peace negotiations. And the Russian peacekeeping forces’ claimed ignorance of the situation on the ground incited harsh criticism from the Azerbaijani authorities a few months ago (see EDM, July 21).

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan continues to push for a new overland corridor link to its Nakhchivan enclave (the so-called Zengazur corridor, via southern Armenia), with the hope of transforming it into the main regional transit route and a direct connection to Turkey. Moreover, Baku argues that this route can simultaneously be utilized by Iran to increase the latter’s trade volume with Armenia without further infringing on Azerbaijani sovereignty (Kommersant, October 5). But a year since the Second Karabakh War, negotiations over the route did not score any significant results. As a result, Baku cut off Iranian trade with the de facto regime in Karabakh. Its intent was to convince the Armenian government to 1) avoid similar provocations and 2) establish the proposed Zengazur corridor link, which could benefit all sides. This unbending position by Baku finally seemed to pay off in October 2021, when Tehran publicly issued a ban on Iranian “private companies” from sending any more trucks to Karabakh (Iranitl, October 20).

The issue of new regional routes was a key topic of negotiations during the meeting of Azerbaijani President Aliyev, Armenian Prime Minister Pashinan and Russian President Vladimir Putin, in Sochi, on November 26 (Civilnet, President.az, November 26). Leading up to the trilateral talks, Yerevan rejected reports regarding a new agreement, and Baku pointedly avoided commenting on the issue (Azatutyun, October 25). Nevertheless, Armen Grigorian, the secretary of the Armenian Security Council, said that “it is possible to discuss a transport link to Nakhchivan via Armenian territory using the Khndzoresk–Bichanak direction. It is still being discussed” (BBC News—Azerbaijani service, November 12). According to Putin, during the Sochi negotiations, the Armenian and Azerbaijani sides agreed to unblock the regional transit corridors that have been at issue since the end of the Second Karabakh War; but working groups must still propose workable timetables and conditions. In any case, some clarity on this subject should be available before this year’s end (President.az, November 26).

Undoubtedly, Azerbaijan will take all necessary measures to prevent the usage of the Lachin corridor as a supply gate of the regime in Karabakh. So for Tehran, to avoid again inflaming tensions with Baku, it will need to pursue options that avoid violating Azerbaijani territorial integrity.